WHAT ARE WINE YEASTS?

Yeasts play a key role in wine production – they transform the sugars in musts into ethanol and carbon dioxide, and are therefore responsible for good outcomes in the vinification process.

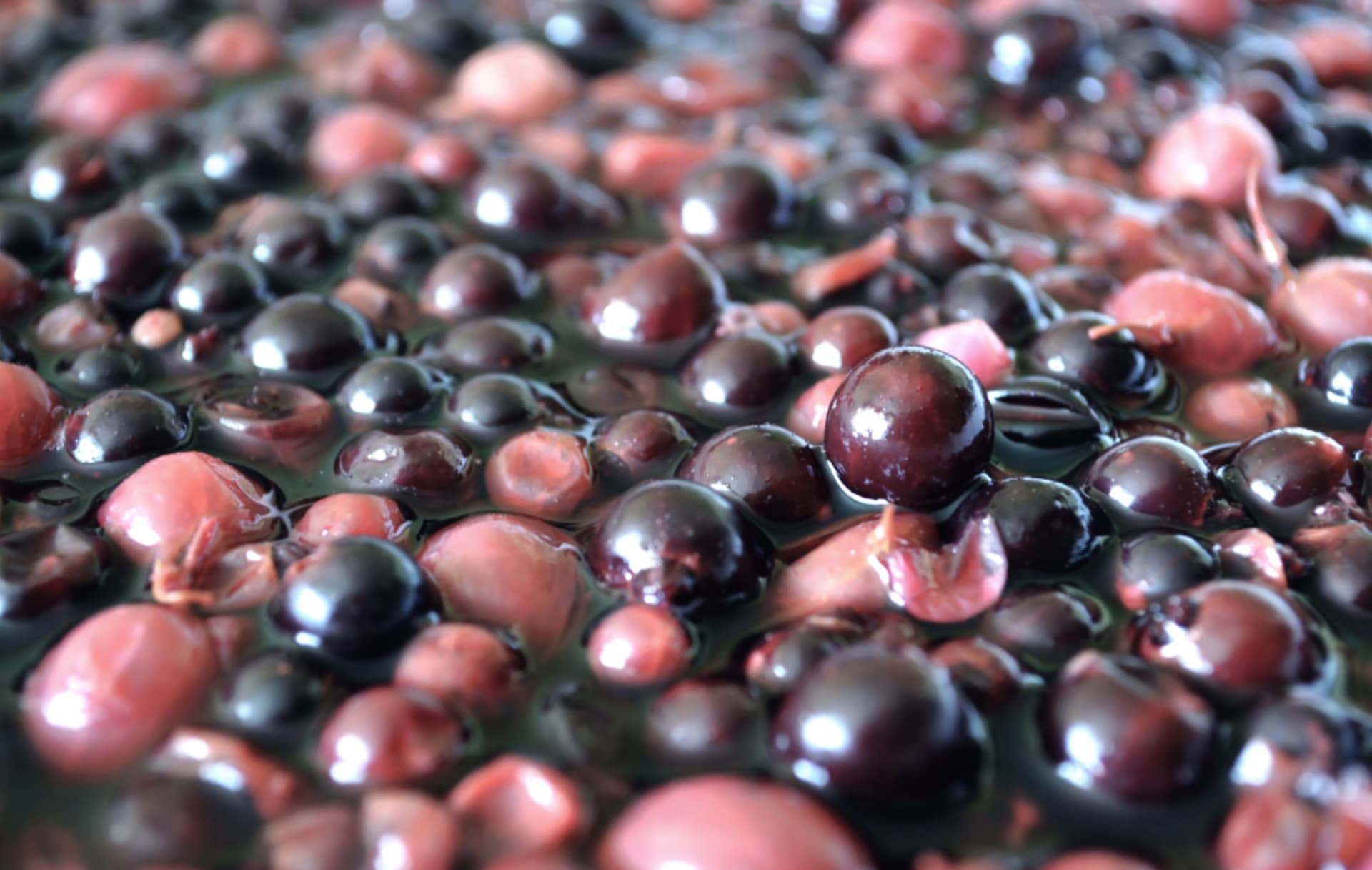

Single-celled fungi with a spherical, oval or elliptical shape, yeasts are infinitesimal in size (5-30 μm long by 1-5 μm wide). Their presence is negligible on unripe grapes but become more substantial as the grapes ripen.

It is the yeasts that set in motion the biochemical process known as fermentation. The must contains all the nutrients that the yeasts need, in a form that they can use. On the other hand, most micro-organisms are not able to use the glucose and fructose contained in the must because of its low pH. During grape crushing, therefore, although all the nutrients escape from the grapes and mix with the microflora on the skin and stalks, the acidity of the pH ‘kills’ almost all the bacteria. Only yeasts and a few bacteria are able to proliferate, and thus to ferment the wine.

WHAT WINE YEASTS ARE USED FOR

The end concentration of ethyl alcohol is therefore determined by the sugars naturally present in the must and then transformed by the yeasts. These, which may be indigenous or selected, are key in determining the quality and characteristics of the wine.

In spontaneous alcoholic fermentation, with no selected yeasts, yeasts of different species interact with each other via a complex biochemical process. Since it is these different yeasts that drive the fermentation process and provide pleasant, balanced wines, it is essential to discover their characteristics and interactions.

In guided fermentation, on the other hand, fermentation is carried out by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The vigorous fermentation action of this yeast, coupled with its resistance, make it the go-to choice when considering vinification using starter cultures.

INDIGENOUS YEASTS

Other yeasts on the grapes or in the cellar environment can intervene during the production or ageing stages and alter the final quality of the wine. For example, during refinement in barrels, the yeast Brettanomyces Bruxellensis can contaminate the wine and synthesise unpleasant notes of horse perspiration. In addition, at the termination of fermentation, excessive contact with oxygen must be avoided when storing the wine, as wine flowers may occur. This is a wine disease that manifests itself as a whitish veil on the surface and is caused by yeasts with aerobic metabolism.

It is important to understand that yeast biodiversity is primarily influenced by the location and conditions in which the grapes are established and grow. There are two main habitats – grapes and must. The former, subject to climatic variability and the actions of man, contains few sugars that can be used by the yeasts (which is why most of them do not survive in the must). When harvested, the habitat changes and other yeasts become predominant. Selection continues and then intensifies with the must system, due to its low, acidic pH. It is at this stage that the main yeasts of this particular vinification process make their way in.

SELECTED YEASTS

An alternative to spontaneous alcoholic fermentation is guided fermentation, i.e. using selected yeasts added to the must.

The most commonly used wine yeasts are the S. cerevisiae yeasts, which were discovered on malt at the end of the 19th century and which today are the best-known micro-organism in all its aspects. Their importance is such that when we talk about wine yeasts, we really mean S. cerevisiae. Highly tolerant of ethanol and capable of development under a variety of conditions, among all yeasts, they are the ones capable of producing the greatest quantity of ethyl alcohol with the same quantity of sugar in the must.

These yeasts, mainly sold in the form of Active Dry Yeasts (ADY), are added to the pressed must. Since S. cerevisiae strains are very different from each other, it is essential to choose the right starter culture composition by considering aspects such as fermentation vigour and fermentation power. And, therefore, the ability to rapidly initiate fermentation by gaining the upper hand over the other micro-organisms in the must, and the ability to withstand the effects of ethyl alcohol. Furthermore, resistance must be assessed of the added yeasts to technological compounds (such as sulphur dioxide and any phytochemicals used in vineyards) and their ability to produce ‘secondary’ compounds capable of influencing the aromatic component of the wine. Indeed, yeasts can produce aromatic compounds such as esters, which endow wine with fruity notes, or they can act using their enzymes, releasing the precursors present in aromatic grapes. For example, for varieties characterised by ‘silent’ aromatic compounds, such as Sauvignon blanc, yeast plays an even more important role, as it allows the varietal aroma to be fully expressed.

China

China

United Kingdom

United Kingdom