-

AEB

- AEB

-

About

- About

-

Group

- Group

-

Info & Contacts

- Info & Contacts

-

Sustainability

- Sustainability

-

OENOLOGY

- OENOLOGY

-

- Biotechnology

-

- Sanitation

-

- Equipment

-

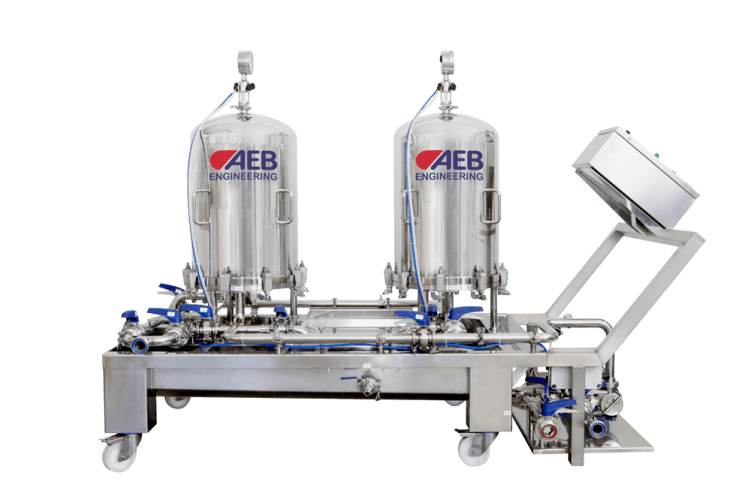

- Filtration

-

BEER

- BEER

-

- Biotechnology

-

- Sanitation

-

- Equipment

-

- Filtration

-

- AEB Brewing lifesyle

-

FOOD

- FOOD

-

- Biotechnology

-

- Sanitation

-

- Equipment

-

- Filtration

-

NEXT

- NEXT

-

- HARD SELTZER

-

- DEALCOLIZED WINE

-

- CIDER

-

CIDER

CIDER

-

Discover AEB Cider

Discover AEB Cider

-

- Cider range

-

-

Sustainability

- Sustainability

CIDER

CIDER

Australia

Australia

China

China

Germany

Germany

Hungary

Hungary

United Kingdom

United Kingdom